Your Cart is Empty

August 10, 2022 8 min read

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are characterized by chronic and recurring symptoms that influence the gastrointestinal tract. Among these disorders, Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is by far the most common and best researched in the scientific literature (1).

Although these disorders are generally not life-threatening, it causes a dramatic decline in the quality of life of sufferers. In fact, after the common cold, IBS is considered to be the main cause of work or school absenteeism in the USA (2).

Aside from the physical discomfort caused, some of the symptoms may cause embarrassment, social isolation, and associated mental health problems (3).

Therefore, intestinal diseases like irritable bowel syndrome should not be overlooked as an important impediment to overall health.

Some of these symptoms include:

These gut disorders are further exacerbated by the use of antibiotics, stress, and an inappropriate diet.

To find out more about these disorders, continue reading here.

Although there is no current cure for FGIDs like IBS, research has led to the development of some effective treatment strategies that could alleviate symptoms significantly.

Here we will discuss two of the main strategies currently followed to support gut health and symptoms of intestinal disorders.

Back in 2005, researchers discovered that ingestion of specific foods triggered the onset of severe symptoms of FGIDs in some people (4,5).

Although many of these foods are seemingly healthy, they can have a profound impact on those who suffer from IBS and other similar gut disorders. These foods are generally poorly absorbed, rapidly fermentable carbohydrates that were collectively called FODMAP foods.

The FODMAP acronym stands for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, And Polyols.

In healthy individuals, FODMAP foods are not digested in the small intestine of the human digestive tract. Instead, they move to the large intestine where they are easily fermented by the bacteria that inhabit the colon.

People who suffer from FGIDs are either completely or partially unable to digest these high-fiber foods in the large intestine. This could be due to combinations of either a physical disruption to the mechanisms of digestion in the colon or a disruption to the gut microbial populations that reside therein (4,5).

Numerous studies have shown that a diet limiting FODMAP food intake is a successful therapy for FGIDs patients (6).

For example, in more than 70% of patients, IBS symptoms were alleviated when avoiding FODMAP foods after a 21-day period (7).

Despite ongoing criticism of this approach due to its highly restrictive nature, a low FODMAP diet remains one of the most common interventions to limit the symptoms of FGIDs.

Prebiotics serve as food for gut microbiota.

These compounds are found in high-fiber foods and are not readily broken down in our digestive systems, but rather consumed by beneficial microbes that aid in digesting food in the gastrointestinal tract (8).

A diet lacking in prebiotics could lead to an imbalance in the populations of gut microorganisms, also known as gut dysbiosis. As a consequence, harmful gut microbes could dominate over beneficial ones, causing a systemic inflammatory response that aggravates the symptoms of gut disorders like IBS.

Clinical trials have shown that supplementation with prebiotics showed a dramatic change in patients suffering from IBS.

The treatment caused an increase in beneficial Bifidobacteria populations in the gut, along with a dramatic decrease in flatulence and bloating. Patients who received this treatment also reported an overall improvement in their perceived symptoms, compared to patients who received the placebo (9).

A balanced diet, rich in high-fiber foods might include a sufficient amount of prebiotics, naturally:

An example of a powerful prebiotic is Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs).

HMOs are non-digestible carbohydrates present in large quantities in human breast milk. A strong link has been established between HMOs and the treatment of IBS (10).

These HMOs, although highly beneficial in infant feeding, are now being synthesized to provide these powerful benefits in supplement form to people of all ages.

The jury is still out on whether prebiotics in supplement form is as effective as ingesting them from food. However, limited research has shown that supplements could support a diet otherwise lacking in dietary prebiotics (11).

You’ve read through the food lists and you are confused. How can some seemingly detrimental high FODMAP foods also be considered beneficial prebiotics for FGIDs?

Don’t worry. You are not alone.

This contradiction has scientists scratching their heads too.

In a recent study published in Gastroenterology, researchers addressed this paradox by studying the efficacy of both treatments: a low FODMAP diet and prebiotic supplementation in treating patients with FGIDs (11).

To no surprise, the outcomes of these vastly different treatments were practically opposite when observing the gut microbiota of these patients.

Beneficial Bifidobacteria were significantly increased in the prebiotic treatment group, whereas these microbes were reduced as a result of a low FODMAP diet.

Despite this strong difference in gut microbiota, the patients from both treatment groups experienced significant improvement in most IBS-related symptoms. These included flatulence, pain, distension, and bloating.

Once the four-week study concluded, patients were further observed for 2 weeks. Interestingly, the prebiotic supplement group enjoyed the benefits of the treatment up to 2 weeks after the treatment had ended. In contrast, the low-FODMAP diet group suffered IBS-related symptoms as soon as their low FODMAP diet came to an end (11).

As our knowledge about FGIDs expands, so will our treatment options.

But formulating an appropriate treatment plan will always start with an accurate diagnosis.

When it comes to FGIDs, their symptoms are overlapping, but their causes and severity vary dramatically. Furthermore, an inappropriate diagnosis for a unique disorder could have detrimental consequences due to an incorrect treatment strategy.

For example, most high FODMAP foods are good for you if you are able to digest them.

Therefore, seeking a knowledgeable, focused medical support team to properly diagnose your condition, should be first priority when it comes to treating FGIDs.

The treatment of FGIDs is not a one-size-fits-all solution.

In fact, it should include an ongoing, dynamic treatment plan that can be altered under medical supervision.

Here are some of the potential strategies, revealed by recent scientific findings:

Because prebiotic treatment showed more prolonged benefits than a low FODMAP diet when treating FGIDs, researchers proposed that patients should be monitored under intermittent prebiotic supplementation (11).

This strategy could have prolonged benefits, even without ongoing treatment. Furthermore, sustaining a restrictive diet of any kind has a proven high failure rate.

According to this strategy, patients with FGID could experience reduced severity in symptoms while maintaining a relatively “carefree” lifestyle by excluding the need for restrictive dieting.

Despite concerns about following a restrictive diet long-term, the low FODMAP diet has been extensively studied and remains the most common treatment strategy for the treatment of FGIDs like IBS.

Fortunately, our understanding of these FODMAP foods is also expanding and so are the related treatment strategies.

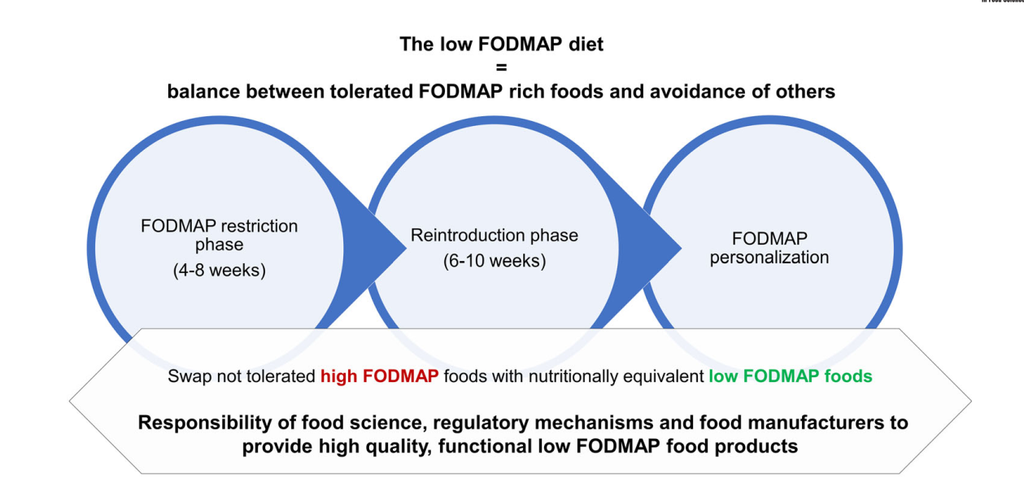

Recently, these FODMAP-related treatment plans were reviewed and a proposed strategy for effective, long-term treatment of the symptoms of FGIDs was proposed. Their proposal is summarized in the figure below (Figure 1; 12).

Figure 1. Low fermentable oligosaccharides. Disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) diet and the importance of nutritious functional low FODMAP products (directly from Ispiryan et al., 2021).

According to this strategy, a sustainable low FODMAP diet must not exclude all fermentable dietary fiber, but simply those that cause gastrointestinal symptoms on an individual case-by-case basis.

They recommend several phases to firstly restrict all FODMAPS, followed by systematic reintroduction of FODMAP foods, followed by a personalization phase, all undertaken under monitoring by a medical doctor and/or registered dieticians (12).

The symptoms and severity of FGIDs are as diverse as those who suffer from them. Therefore, treatment strategies should be no different.

Research has revealed that variations of a low FODMAP diet and supplementation with prebiotics (such as HMO prebiotics) are two of the most promising treatment options to explore.

Under the appropriate medical supervision, dramatic improvements can be made in the quality of life of patients suffering from FGIDs like IBS through the formulation of tailor-made treatment plans with long-term efficacy.

Written By:

Kari du Plessis, Ph.D. in Biotechnology, who enjoys writing about holistic health topics.

April 14, 2024 7 min read

April 11, 2024 7 min read

April 05, 2024 6 min read

Get the latest gut health content and a 10% off discount on your first order